Bridging Structure and Meaning: The Impact of Story-Listening on Language Processing

Dissecting Language: Simplifying Complex Sentences through Story-Listening

The Story-Listening (SL) method dissects sentences and simplifies them, breaking them down into smaller, more manageable structures within a sentence. It also explains a sentence's deeper meaning.

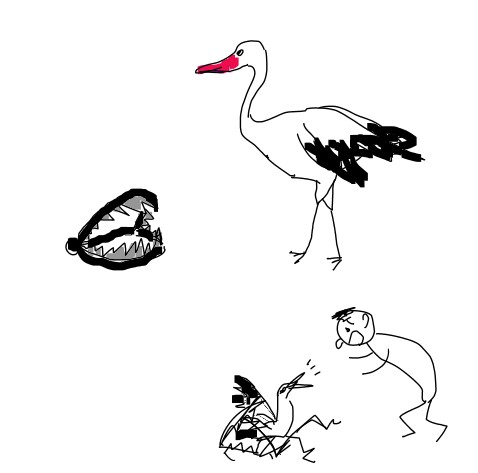

For example, the sentence "The crane had a large wing caught in a trap" would be presented like this while the teacher draws the bird, beak, wing, man, and trap:

- There was a bird.

- It was a white bird.

- It was a big white bird.

- The bird had large wings.

- The wings had black feathers.

- The bird had a long beak.

- The beak is the mouth of a bird.

- It is a crane.

- It is NOT a crow.

- A crow is a black bird.

- The man saw a crane.

- The crane was in trouble.

- Its wing was caught in a trap.

- A trap is a tool that catches animals, like a mouse or a rabbit.

- Its wing was in a trap.

- The crane could not move.

- The trap caught the crane's wing.

- The wing was caught in a trap.

Then, the teacher presents the target sentence in text and writes it on the board:

"The crane had a large wing caught in a trap."

Breaking the narrative into smaller, focused sentences allows for better understanding and retention.

You can give different example sentences:

- “The raccoon had its head stuck in a bottle.”

- “The whale had its body trapped in the fishing net.”

The SL method introduces underlying basic sentences to make the target sentence comprehensible for foreign language learners, presenting a surface structure as new information. Using natural review with familiar structures as a stepping stone for a new structure is helpful for both reinforcing the old and acquiring the new language.

Load Reduction for Students

One advantage of the SL method is that teachers do the work to help students understand quickly, rather than having them search for answers regarding word meanings, pronunciation, spelling, and usage in sentences.

The Role of Unified Input in Literacy Development Through Story-Listening

I stress the importance of SL for continued sessions as unified input because this method effectively introduces the meanings of complex surface structures to prepare students for reading. This approach fosters a supportive environment for language acquisition as students actively engage with the language they are acquiring and learning.

Overall, our work with SL and GSSR reflects the principles of effective language acquisition emphasized in the Input Theory (1982, 1985, 2003). It also resonates with a broader understanding of how we naturally acquire language.

Sources

Krashen, S.D. (1982). Principles and practices in second language acquisition. New York: Prentice-Hall. http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_practice.pdf

Krashen, S.D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Culver City,

CA: Language Education Associates.

Krashen, S. (1989). We acquire vocabulary and spelling by reading: Additional evidence

for the Input Hypothesis. Modern Language Journal, 73(4), 440-463.

Krashen, S.D. (2003). Explorations in language acquisition and use: the Taipei lectures.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Krashen. S.D. http://www.sdkrashen.com

Krashen, S., & Mason, B. (2022) Foundations for Story-Listening: Some basics. Language Issues, 1(4), 1-5. http://language-issues.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/4-1.pdf

Krashen, S., & Mason, B. (2020). The optimal input hypothesis: Not all comprehensible input is of equal value. CATESOL Newsletter (May). https://www.catesol.org/v_newsletters/article_151329715.htm

Mason, B., & Krashen, S. (2020). Story-Listening: A brief introduction. CATESOL Newsletter, July, 53(7). https://www.catesol.org/v_newsletters/article_158695931.htm